Acid reflux, commonly experienced as heartburn, is a widespread digestive issue affecting millions. It occurs when stomach acid flows back up into the esophagus—the tube connecting your mouth to your stomach. This backward flow can irritate the lining of the esophagus, causing that burning sensation we associate with acid reflux. While occasional acid reflux is usually not a cause for concern, chronic or frequent episodes may signal an underlying issue, and one common connection lies with a condition called hiatal hernia. Understanding this relationship is crucial for managing symptoms and potentially preventing further complications.

Hiatal hernias aren’t necessarily the sole cause of acid reflux, but they significantly contribute to its development and severity in many individuals. They represent a structural abnormality that weakens the barrier between the stomach and esophagus, making it easier for acid to travel upwards. This isn’t always immediately apparent; many people live with small hiatal hernias without ever experiencing noticeable symptoms. However, when reflux becomes persistent or problematic, investigating whether a hiatal hernia is involved becomes essential for effective diagnosis and treatment strategies. The interplay between these two conditions often requires a nuanced approach to care, focusing on both symptom management and addressing the underlying structural issue if necessary.

Understanding Hiatal Hernias

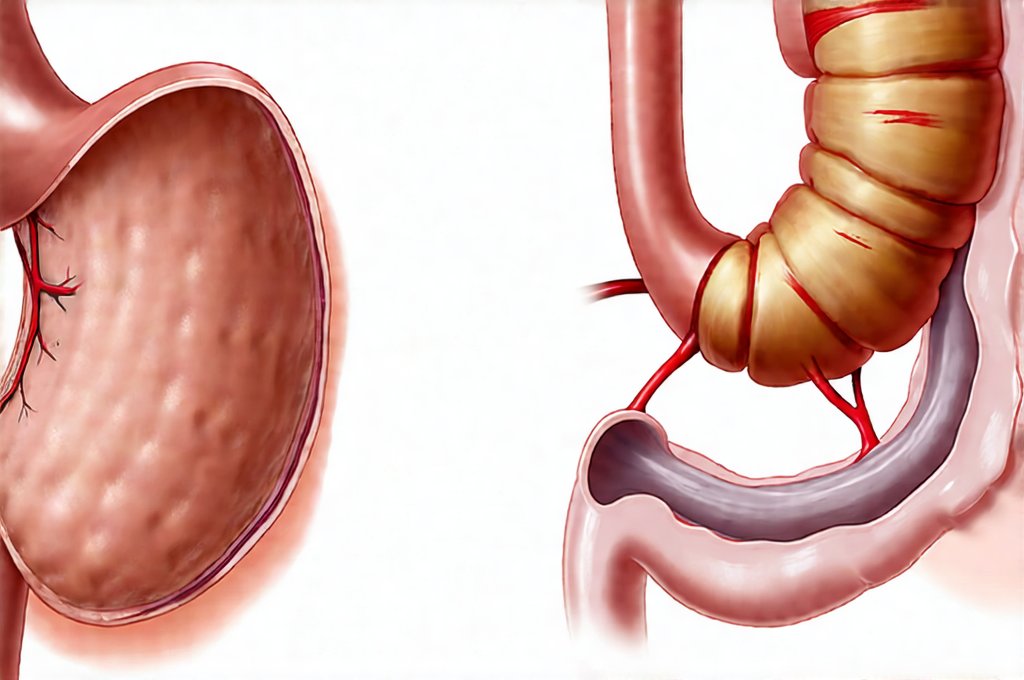

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of your stomach bulges up through an opening in your diaphragm—the muscle that separates your chest from your abdomen. Normally, this opening (the hiatus) allows only the esophagus to pass through. However, in a hiatal hernia, a portion of the stomach pushes upwards, creating a sac-like protrusion above the diaphragm. There are primarily two types: sliding hiatal hernias and paraesophageal hernias. Sliding hernias, the more common type, involve the stomach and gastroesophageal junction (where the esophagus meets the stomach) sliding up through the hiatus. Paraesophageal hernias occur when part of the stomach remains in the abdomen but a portion protrudes alongside the esophagus.

The exact cause of hiatal hernias isn’t always clear, but several factors can contribute to their development. These include aging (weakening of diaphragm support), chronic straining (from constipation or heavy lifting), obesity, and pregnancy. It’s important to note that many people with sliding hiatal hernias don’t experience symptoms, meaning they are often discovered incidentally during tests for other conditions. When symptoms do occur, they frequently overlap with those of acid reflux, making it difficult to distinguish between the two without proper medical evaluation. The hernia itself can disrupt normal esophageal function and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone which is a muscle that prevents stomach acid from flowing back up.

The presence of a hiatal hernia doesn’t automatically mean you’ll experience significant problems, but it does increase the likelihood of developing chronic acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Because the stomach is positioned higher in the chest when a hernia is present, gravity works less effectively to keep stomach contents down. Additionally, the altered anatomy can affect the LES, making it more prone to relaxing and allowing acid to escape. This creates a vicious cycle: the hernia contributes to reflux, and chronic reflux can potentially worsen the hernia over time.

The Acid Reflux Connection & GERD

Acid reflux is often described as a symptom, while GERD is considered the disease resulting from frequent or severe acid reflux. A hiatal hernia can significantly exacerbate GERD symptoms. While not everyone with GERD has a hiatal hernia, its presence frequently worsens the condition and makes it more resistant to conventional treatments. The structural change caused by a hernia disrupts the natural pressure gradient that keeps stomach acid where it belongs. This disruption, combined with a weakened LES (which is common in both conditions), allows for more frequent and prolonged exposure of the esophageal lining to corrosive stomach acid.

Chronic acid reflux can lead to several complications beyond just heartburn. These include esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus), esophageal ulcers, Barrett’s esophagus (a precancerous condition where the esophageal lining changes), and even an increased risk of esophageal cancer. The presence of a hiatal hernia amplifies these risks because it creates a more challenging environment for healing and recovery. Addressing both the acid reflux and the underlying hiatal hernia is often crucial to mitigate these long-term consequences. Lifestyle modifications, such as dietary adjustments and weight management, can help manage symptoms, but sometimes medication or surgery may be necessary.

Diagnosing Hiatal Hernias & Acid Reflux

Diagnosing a hiatal hernia typically involves a combination of medical history review, physical examination, and diagnostic tests. If your doctor suspects you have a hiatal hernia, they might recommend one or more of the following:

- Endoscopy: This is often the primary method for diagnosis. A thin, flexible tube with a camera (endoscope) is inserted down your esophagus to visualize the lining and check for hernias, inflammation, or other abnormalities.

- Barium Swallow (Esophagram): You drink a barium solution, which coats the esophagus, allowing it to be seen clearly on X-rays. This can help identify the size and type of hiatal hernia.

- pH Monitoring: Measures the amount of acid in your esophagus over a period of time (usually 24 hours) to assess the severity of acid reflux.

- Esophageal Manometry: Evaluates how well the muscles in your esophagus are functioning, including the LES, and can help identify problems with esophageal motility.

Diagnosing acid reflux typically relies on symptoms and may involve similar tests like endoscopy and pH monitoring to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other conditions. It’s essential to differentiate between occasional heartburn and chronic GERD to determine appropriate treatment. Your doctor will likely ask about your symptoms, frequency of episodes, triggers, and any alleviating factors.

Lifestyle & Dietary Modifications

Managing both hiatal hernia and acid reflux often begins with lifestyle and dietary modifications. These changes can significantly reduce the frequency and severity of symptoms:

- Dietary Changes:

- Avoid trigger foods such as fatty or fried foods, spicy foods, chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated beverages.

- Eat smaller, more frequent meals rather than large ones.

- Stay upright for at least 3 hours after eating.

- Lifestyle Adjustments:

- Elevate the head of your bed by 6-8 inches to help prevent acid reflux while sleeping.

- Lose weight if you are overweight or obese, as excess weight can put pressure on your abdomen.

- Avoid tight-fitting clothing which may increase abdominal pressure.

- Quit smoking, as smoking weakens the LES.

These modifications aim to reduce stomach acid production, prevent it from flowing back into the esophagus, and minimize irritation of the esophageal lining. While these changes can be effective for many people, they might not be enough to fully manage symptoms in all cases.

Medical & Surgical Interventions

When lifestyle and dietary changes aren’t sufficient, medical or surgical interventions may be considered. Medications commonly used to treat GERD associated with hiatal hernias include:

- Antacids: Neutralize stomach acid for quick relief of heartburn.

- H2 Blockers: Reduce the amount of acid produced by the stomach.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): More potent than H2 blockers, they significantly reduce acid production. Long-term use should be discussed with your doctor.

In some cases, surgery may be recommended, particularly for large paraesophageal hernias or when medications are ineffective. The most common surgical procedure is fundoplication, where the upper part of the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophagus to strengthen the LES and prevent acid reflux. This is generally reserved for patients with severe GERD who haven’t responded to other treatments. It’s important to remember that surgery carries its own risks and benefits which should be carefully discussed with a qualified surgeon.