Fasting has transitioned from an ancient practice steeped in spiritual tradition to a modern wellness trend gaining significant traction. While often associated with weight loss, the physiological effects of fasting extend far beyond simply reducing caloric intake. Increasingly, research is focusing on how fasting profoundly impacts our gut microbiome and its enzymatic activity – the very engines driving digestion and nutrient absorption. This isn’t merely about what we don’t eat during a fast; it’s about the cascade of changes happening within our digestive system as it recalibrates without constant input, creating an environment that can potentially optimize health. Understanding these alterations is crucial for anyone considering incorporating fasting into their lifestyle, and for appreciating the intricate relationship between diet, gut health, and overall wellbeing.

The digestive system isn’t a static entity; it’s remarkably adaptable. When consistently supplied with food, our bodies maintain a baseline level of enzymatic production geared towards processing that consistent intake. Fasting disrupts this pattern, forcing the system to shift gears. This is where the fascinating interplay between fasting and gut enzymes begins. Enzymes are biological catalysts essential for breaking down food into absorbable nutrients. Different enzymes target different macronutrients – amylase for carbohydrates, protease for proteins, lipase for fats. The production of these enzymes isn’t constant; it fluctuates based on dietary habits and metabolic demands. Prolonged or frequent feeding stimulates continuous enzyme release, while periods of fasting lead to a downregulation of this activity, prompting significant changes in both the types and quantities of enzymes produced. This dynamic regulation is central to how fasting impacts gut health and overall metabolism.

The Shifting Landscape of Gut Enzymes During Fasting

Fasting induces a state of metabolic flexibility where the body transitions from primarily utilizing glucose for energy to relying more on stored fat and ketones. This shift directly affects enzymatic activity within the digestive system. When we’re constantly eating, particularly diets high in processed foods or simple carbohydrates, our gut is consistently producing enzymes geared towards breaking down these readily available sugars and starches. However, during a fast, the demand for carbohydrate digestion diminishes significantly. Consequently, the production of amylase – the enzyme responsible for carbohydrate breakdown – decreases. Simultaneously, there’s an increase in enzymes associated with fat metabolism and protein turnover as the body begins to mobilize stored resources. This isn’t just about reducing certain enzymes; it’s a recalibration of the entire enzymatic machinery.

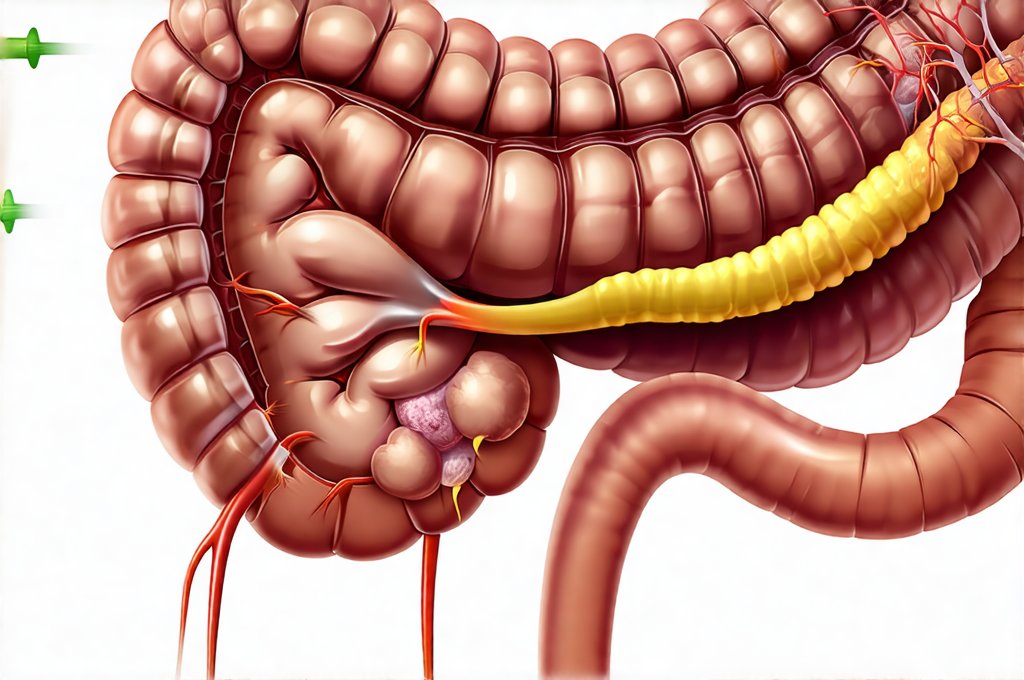

This recalibration extends beyond simply up- or downregulating enzyme production. Fasting can also influence the composition of gut microbial communities, which themselves produce various enzymes essential for digestion and nutrient processing. The gut microbiome is incredibly diverse, containing trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms. These microbes play a critical role in breaking down complex carbohydrates that human enzymes cannot digest, synthesizing vitamins, and modulating immune function. Changes in dietary intake – or lack thereof during fasting – can dramatically alter the balance of these microbial populations, leading to shifts in their enzymatic output. For instance, reducing carbohydrate intake through fasting may favor bacterial species capable of utilizing alternative energy sources like fiber or ketones, leading to an increase in enzymes involved in their metabolism.

The impact on digestive enzyme production isn’t uniform across all types of fasting. Intermittent fasting (IF), characterized by regular cycles of eating and fasting, typically results in more moderate enzymatic changes compared to prolonged water-only fasts. In IF, the periods of feeding still provide some stimulation for enzyme production, preventing a complete shutdown. Prolonged fasts, on the other hand, induce a more substantial downregulation of digestive enzymes as the body relies almost entirely on endogenous resources (stored fat and protein). This difference highlights the importance of understanding the specific fasting protocol employed when considering its impact on gut health and enzymatic function. Ultimately, the goal isn’t necessarily to eliminate enzyme production, but to restore balance and optimize functionality. You might find more insights in intermittent fasting research.

Enzyme Regulation & Autophagy

One of the most compelling aspects of fasting is its ability to induce autophagy, a cellular “self-cleaning” process where damaged or dysfunctional cells are broken down and recycled. This process extends to gut cells as well, including those responsible for enzyme production. During prolonged feeding, these cells can become overloaded with metabolic waste products, potentially impairing their function. Fasting provides an opportunity for autophagy to clear out this cellular debris, effectively “resetting” the enzymatic machinery of the gut. Autophagy isn’t just about removing damaged components; it also promotes cellular renewal and regeneration, leading to healthier and more efficient enzyme production over time.

This link between fasting, autophagy, and enzyme regulation has significant implications for long-term gut health. By regularly initiating autophagy through periods of fasting, we can potentially prevent the accumulation of dysfunctional gut cells and maintain a robust enzymatic capacity. However, it’s crucial to note that autophagy isn’t always linear. Factors like age, genetics, and underlying health conditions can influence its effectiveness. Furthermore, prolonged or excessively restrictive fasting may actually suppress autophagy in some individuals, highlighting the need for personalized approaches. Thinking about diet? Consider vegetarian diet options.

Microbial Enzyme Contributions

As mentioned earlier, gut microbes aren’t passive bystanders; they actively contribute to enzymatic digestion. Different microbial species possess different enzymatic capabilities, allowing them to break down a wide range of compounds that human enzymes cannot handle. For example, certain bacteria produce enzymes capable of degrading complex polysaccharides found in plant fibers, releasing nutrients like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which are vital for gut health and overall wellbeing. Fasting can alter the composition of the microbiome, leading to changes in the abundance of these enzyme-producing bacteria.

Specifically, reducing carbohydrate intake during fasting can decrease the population of saccharolytic bacteria – those that thrive on sugars – while potentially favoring species capable of utilizing other substrates like fiber or ketones. This shift can result in an increase in enzymes involved in fiber fermentation and SCFA production, contributing to a healthier gut environment. It’s important to remember that this microbial adaptation is gradual and depends on the duration and frequency of fasting as well as individual microbiome composition. A diverse and resilient microbiome is essential for maximizing the benefits of fasting. If you’re craving something after fasting, rich and salty options can be satisfying.

Re-Feeding & Enzymatic Recovery

The re-feeding period following a fast is just as crucial as the fasting itself. Abruptly resuming a diet high in processed foods or simple sugars can overwhelm the digestive system and negate many of the benefits achieved during fasting. The gut needs time to gradually readjust to processing food again, and enzymatic production must ramp up accordingly. Introducing easily digestible foods initially – such as bone broth, cooked vegetables, and fermented foods – allows the digestive system to slowly regain its functionality without being overloaded.

This gradual re-feeding approach supports optimal enzyme production and minimizes the risk of digestive discomfort. Furthermore, continuing to prioritize nutrient-dense, whole foods after fasting helps maintain a healthy gut microbiome and sustains the enzymatic adaptations achieved during the fast. Ignoring this crucial phase can lead to bloating, gas, diarrhea, or other digestive issues, indicating that the gut hasn’t fully recovered its ability to efficiently process food. This highlights the importance of viewing fasting not as an isolated event, but as part of a holistic lifestyle approach focused on nourishing both the body and the microbiome. When life gets busy, home late meals can be lifesavers.